by Molly Hankwitz, June 2020.

The Suicide Club, pre-cursor to the more notorious Cacophony Society, was founded by Gary Warne, Adrianna Burk, David Warren and Nancy Prussia in San Francisco in 1977 and was finished by about 1982.

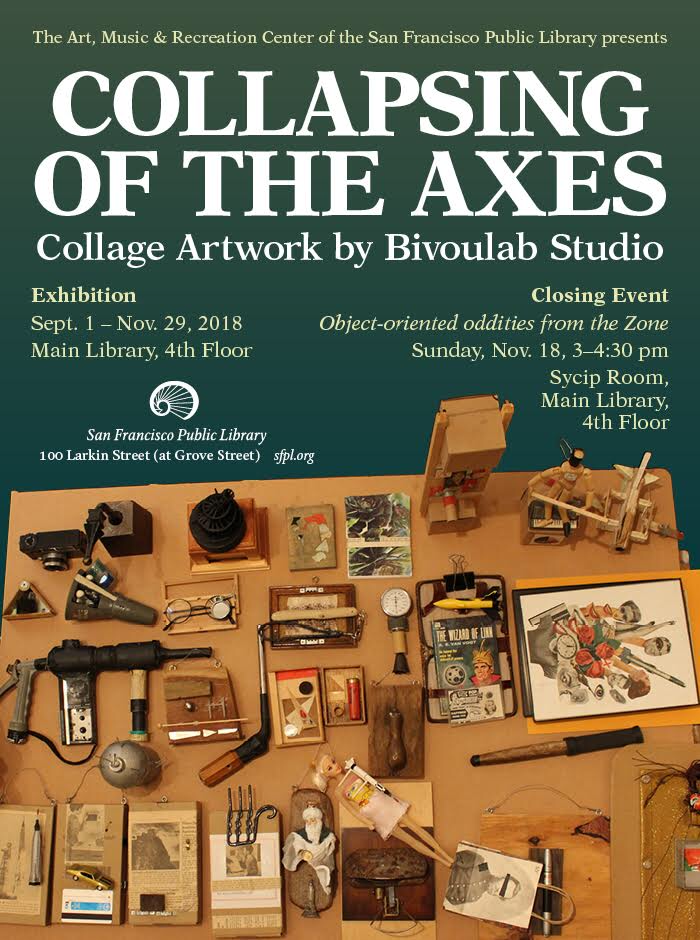

Pro Arts gallery, Oakland, held a talk on the Club as part of the retrospective exhibition SIGNMAN: JOHN LAW curated by Natalia Mount. The talk was certainly an open nod to the ideas and the friendships forged in the ultimate “now” of being around at that time, and searching for the soul of creative practice. At the same time as a contemporary gallery talk, the substance of the Club’s activity was showcased to a new, younger audience and gave depth to knowing the work of John Law, Oakland artist. The gallery space was full of Law’s art and audience and one time members of the Club were peppered throughout. Cacophony Society leader, and co-creator of early Burning Man events, John Law, and Don Herron, Suicide Club member and founder of the Dashiel Hammett walking tours in San Francisco were both present and engaged us with lively conversation.

Such underground groups and events have scant representation in scholarship. The anarchical, free-thinking, and unconventional “methodologies”, legendary at the time of their inception, are often difficult to pin down in documents or afterthought. You had to be there. This condition alone leads to their ongoing status. The Situationist International owes much to the ambiguity of their own terms when curious writers and artists speculated upon their past. They are elusive, and until recently given the work of scholars like McKenzie Wark, have regained discursive significance.

In the case of the Suicide Club’s surrealistic escapades, news articles, photographs, and ephemera cannot tell us what it was like to take part. Law and Herron firstly dispelled myths that suicide had anything to do with the Club’s objectives. Nor was suicide or attempted suicide a prerequisite for Club participation as rumors had it. Rather, Club members needed to participate in the street theater and pranks. 30 members rode San Francisco cable cars stark naked and wrote post cards along the way to commemorate the excursion (see links below). Elaborate games in odd locales and urban explorations of abandoned buildings, cemeteries, sewer ways, waterways, and bridges were some of the Club’s “locales”. They also tried “infiltrations”. The Unification Church and The American Nazi Party were particularly impressive for having been infiltrated by the Suicide Club. Such actions resonate with media-hacking performances such as those of The Yes Men.

It is thus difficult to recreate how underground “live” art was received or how it impacted participants. As a history in art it is compelling to revisit the spirit of the time with those who did the work. John Law describes the Suicide Club as semi-formless, ad hoc and action-oriented art group whose claim to secrecy was due to the public nudity or trespassing both are illegal in San Francisco. In newspaper clippings, costumed members appear grinning, suggestive of the delight in getting away with something. Between the top-secret dramatic locations, the scant documentation, and unpublished scripting which took place during their events, their art was liminal or impossible, deliberately defiant of categorization and oriented towards “thrill”. They were made for those who participated. They are similar to the psychogeographic “derives” of the SI; an effort to experience “experience” in a capitalist world; an effort to touch the inner mind and conscience and dream-state of the imagination.

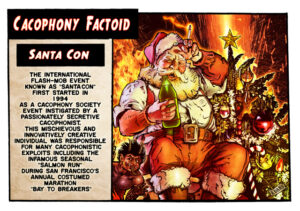

Radical gestures such as public nudity gave the Club its legendary status and that status was once again earned when they morphed into The Cacophony Society, a profoundly non-art collective aimed at the absurd; the dadaist. The Cacophony Society influenced artists and audiences through highly-visible public works. Santacon was an amusing critique of retail commodity culture. When dozens of Santas flood the pre-Christmas retail scene, identically dressed, they present the endlessly reproducible spectacle of capitalist Christmas as its own hall of mirrors. The 2014 publication of The Cacophony Society book, Tales of the Cacophony Society, and John Law’s retrospective reflect upon the comic fun of artmaking.

Other descriptions of the Club’s activities from the Pro Arts talk emphasized the care in planning and the way “members” were included. Participation was had by anyone willing to make the events happen and there was rarely a dull moment in San Francisco’s 1990s art world, when the Cacophony society was around. Art became viewed as an unofficial stream of happily inane events intervening in everyday life.

Cover up

Considering some of the excess and liberation of the San Francisco art scene such as gay liberation art made here when gay rights barely existed elsewhere, or when women’s performance took over in the 1960s and 1970s, it is obvious that the artistic milieu promises something different. In the more madcap events, it was often exclusion from the arts which triggered momentum. San Francisco’s experimental scene has been shelving the white-walled gallery space for decades, and focusing upon uncontrolled bodies and the performance of experience. The Suicide Club challenged normative social reality and the control of public space to say the least. Their disregard for normative values in public safety as purported by the ‘safe’, sends a message of speculative freedom and the more immersive, private experiments were expressions of art-as-engaged-experience not as something still, passive; devoid of participation. Their antics link conceptually, perhaps, to the increasingly “interactive” computerization of culture in the 90s.

Even more so now in the device-oriented world of multiple, small screens, dependent upon device/platform/information and computer-mediated-communication, art can be viewed as a spectacle which circulates and mainstreams its own artifacts. This distanced seeing/experience of “social media” does not replace the art, as much as we attempt to make artforms out of it, and to be connected and networked. Art cannot be learned or performed as a packaged event, or a mere expression of information tourism, reliant upon data and image glut. Art, thus made, falls forever over backwards into its own mistaken quantifications of what is important. The work of art becomes a game.

John Law is a professional artist, a sign painter by trade with a dramatic studio atop the Oakland Tribune tower. His unconventional works have rarely intersected in any predictable way with officialdom. But, as a leader of the Billboard Liberation Front, and “fueled by a single passion: the timely improvement of outdoor advertising” he made climbing up interstate billboards and altering the meaning of advertisements into a revolutionary, culture jamming practice. Always maintaining a career deliberately out-of-bounds, Law has been both catalyst and artist, using the buildings, bridges and billboards of the Bay Area as a backdrop upon which to play, to dream; to ignite relevance and passion. Who the dreams were for, or what the fact of dreaming meant, remains with the players, in the few artifacts, and in the memories.

A Legacy in Art

Conscious formulation of an ethos which embraced artistic freedom and experimentation was part of the Suicide Club’s antics wherein Law scouted for vacant places: waterways, accessible rooftops, empty warehouses, and anchored ships. He and other members would study these locations and how they would use them as an immersive world in a future event. But it is also clear that the mere act of transgressive trespassing and illegality was part of the art; a way of defying law and order thinking and of laying claim to the city. Such was established a methodology in defiance of surveillance, in what the late Cacophony Society artist Cary Galbraith referred to as “the zone”, resonating with Hakim Bey’s “autonomous zones” and the “ambient unity” lamenting of the SI, who rethought Paris as a place of artistic play.

In one of these events, lines of a script and directions were typed on a typewriter as the group progressed, making immediate the operations of the event as it unfolded, and allowing for experimentation in constructs of social relations, much like Yvonne Rainer questioned structures of authority through filmmaking. Thus, props, space, and ideas were in a collective convergence or flow in these Club events, similar to the manner by which VR or “game worlds” adjust according to players’ choices while changing in physical atmosphere. Desire, action, expression rose according to a collective plan or agreement. Once the Club dressed up, each as a different animal, and got on a public bus. “Who was going to arrest a bunch of people dressed as animals?,” Law said with a smile. How much defying of authority could they get away with?

The anti-logic was clear. The Pro Arts audience grinned. “Only about 20 people would know anything at all,” Law stated when asked about secrecy. He then recalled how women members were challenged to learn new skills. Word processing or food preparation would be sidelined for learning to climb three stories by rope or swimming in freezing-cold water. Contemporary “escape rooms” which come with a high priced ticket and reservation or the adult-only “pirate parties” of the 2000s might be considered bourgieous examples of said- relief from lifestyle.

Story

Immersive artworks are now produced with VR and AR. These artforms have a history in experimental film, projection art, and video installation. Immersive, emotional, even learning environments have had two main directions. One, they are designed to allow single or multi-viewer interaction with virtual elements and narratives as part of a “game” type world – the most obvious analogy for immersive display – and open the concept of “world-making” to collective input (think Minecraft) and to “game-changing” where game-space and “storyline” and characters are co-created by viewers/players. Of equal if not greater potential, however, due to its more direct route to the senses, in terms of experience, is the use of programming and visuals to re-direct expectations of game play (frequently the thought processes of military industrial entertainment) in order to produce shocking, surprise effects and experiences for the viewer/participant. In these works, viewers identify with and experience the emotional landscapes of others and learn to judge the formulations of “navigation” from a critical standpoint.

Tamiko Thiel and Zara Houshmand’s (with activist Susan Hayase) VR installation, Beyond Manzanar, first produced in the 1990s, has been recently revamped as an immersive installation and expands on mainstream concepts “game-worlds” to raise questions of “the connection between the racial profiling and scapegoating that led to mass violations of Japanese Americans’ rights and the similar fear and hate-mongering aimed at Iranian Americans during the “Iranian Hostage Crisis” (November 1979 to January 1981) to those who experience the art. Beyond the expectation of play that is inherently part of the VR spatial imagination, Beyond Manzanar is a highly controlled “experience” in which, despite the choices of movement which a participant might expect to “get” or to “want”, the viewer/participants find themselves imprisoned inextricably or bombed from above in locations associated with beauty and peace. The logic of “freedom” is undermined by the reprogramming of spatial expectations, through the subversive mapping of Japanese and Iranian cultural spaces deployed visually and technologically. Arguably, this intent to immerse the viewer in an unfamiliar logic, so as to job them out of their everyday way of seeing is close to the intentions of The Suicide Club when they sometimes took up a perilous ‘playspace’ for the pleasure of experiencing what was unanticipated. Both artistic efforts utilize immersive reality for purposes of experimental investigation into ethical and meaningful action as well as to critique social norms and convention.

Beyond Manzanar stills from video.

John Law’s retrospective, SIGNMAN: JOHN LAW, a collection of neon-works, photographs and small sculptures was enmeshed with themes of transgressive movement. The use of police tape, the adumbrated billboards, even the unlikely publishing of his photographs, billboard and climbing work in media of the time, offer a glimpse into Law the artist who worked to suggest a function for himself as artist within and without convention. Ultimately, the work of John Law, and the Suicide Club, can be read as a deep and authentic understanding of the public and private city as a space upon which anarchy can act, and be rewarded.

The work of The Suicide Club and The Cacophony Society speaks to a lineage of artists who went after uncontrolled expression amidst encroaching surveillance, taxing of flows, gated communities; law and order, hegemony, sexism, and the pervasive privatization of urban life.

—

SIGNMAN: JOHN LAW

Exhibition at Pro Arts Gallery, Oakland, CA.

August 2019

https://proartsgallery.org/event/signman-john-law/

Links and Resources

Photo of the Reenactment of the Summer of Love by Greg Mancuso,

All other photos (with exception of Playland, n.a.) courtesy, Molly Hankwitz.

The Suicide Club archive – https://www.scribd.com/document/213747288/Cacophony-Society-00-Lanc

The Suicide Club chronology of events – http://www.suicideclub.com/events/

Tales of the Cacophony Society – https://johnwlaw.com/2018/08/13/tales-of-the-san-francisco-cacophony-society-pdf-and-news-of-coming-reprint-in-paperback/

Suzanne Lacy Performance/Installation – https://www.suzannelacy.com/performance-installation

Beyond Manzanar – https://sjmusart.org/event/creative-minds-tamiko-thiel-and-zara-houshmand-susan-hayase